All Devils Are Born With a Name

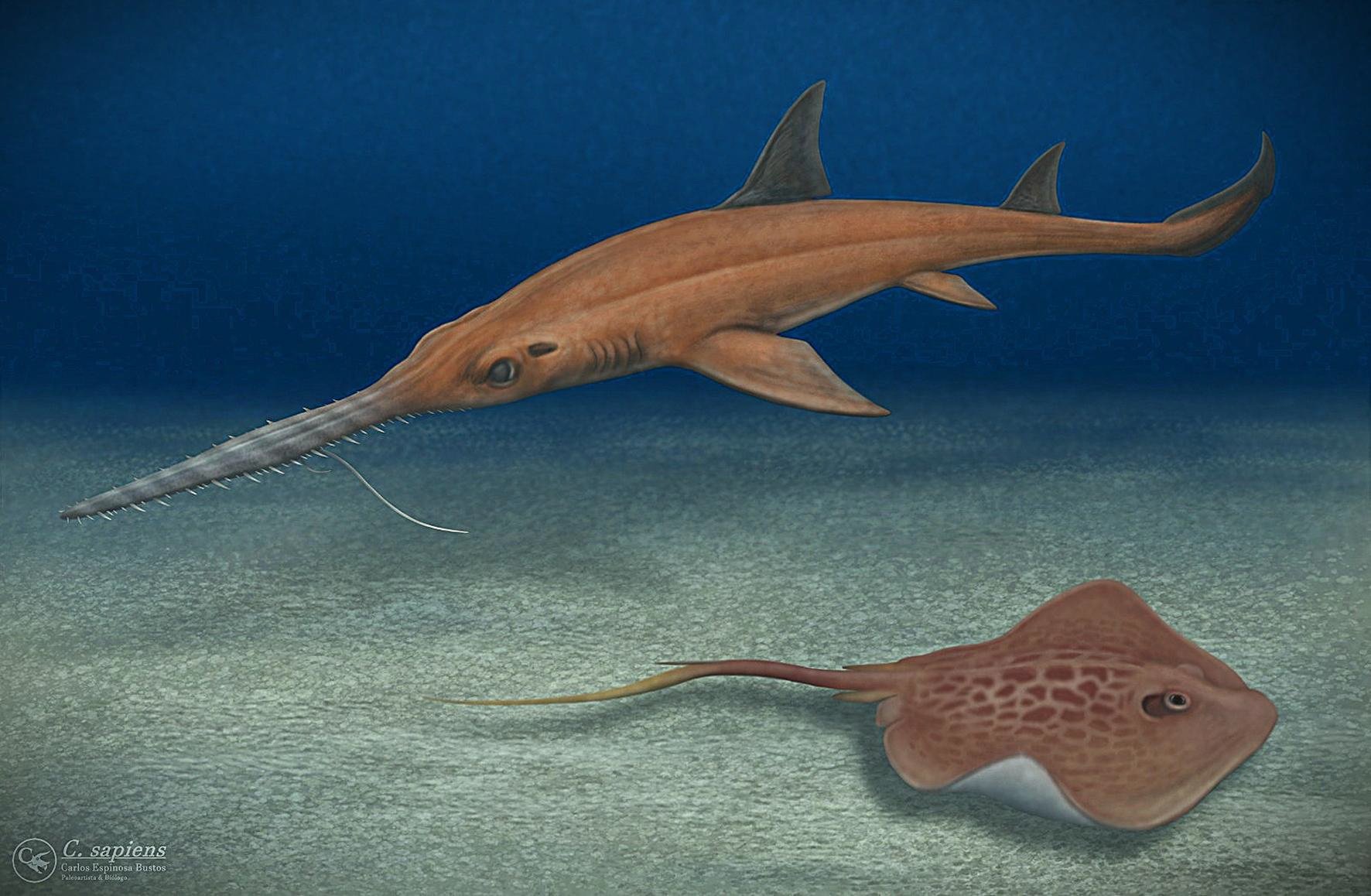

The prehistoric sawshark Pochitaserra patriciacanalae (above) and the ray Dasyatis manuelcamposi (below). Credit: Carlos Espinosa Bustos

Paleontologists can be persnickety about names. Years ago, in a lonely Montana watering hole, I was getting a fry basket dinner with a dinosaur expert who couldn’t hold back his displeasure over the name Brontomerus. The title, given to a long-necked, herbivorous dinosaur with an expansive hip flange for soft tissue attachments, means “thunder thighs.” Such silly names mocked the seriousness of the science, he charged, adding that scientific binomials should be more refined and respectable. For example, he proposed, he was saving a name for a new species in his back pocket inspired by the Marquis de Sade. I only snickered to myself a little as I tipped my beer back.

Scientific names have always said more about the researchers choosing the names than the organisms themselves. And even in the early days of paleontology, when knowledge of Greek and Latin names was part of a college education and thus a mark of class, experts were so intent on coining new names to bolster their control over the natural world that we wound up with titles like Allosaurus - “different lizard,” simply because the fragmentary remains were different than others seen before and O.C. Marsh was too busy trying to out-fossil his rival E.D. Cope to wait for a more informative specimen. Naming a fossil organism is a rare privilege, and one that should be given careful consideration, but there is no standard of refinement or deference to class that should dictate the rules for all. If anything, I’m thrilled when prehistoric creatures get dorky names. Like Pochitaserra.

If you’re a Chainsaw Man fan, you’re one step ahead of me here. And if not, perhaps you haven’t yet heard of the adorable little chainsaw puppy demon that plays an essential part of the popular, bloody, ridiculous manga and anime franchise. Either way, Pochita is an apt inspiration for a name given to a collection of 7 million-year-old teeth found in the Atacama Region of Chile.

A sawshark-transformed Pochita. Credit: Cotty Charuri

The shark’s full name is Pochitaserra patriciacanalae, as announced in Papers in Palaeontology. It means “Patricia Canales’ Pochita saw,” the species name honoring the memory of the paleontologist for her work on marine fossils in Chile.

So far, relatively little is known of Pochitaserra. Prehistoric sharks, like their modern counterparts, had skeletons primarily made of cartilage. Cartilage is more likely to decay away than fossilize. But shark teeth are much harder than the rest of their skeletons, more prone to fossilize, and are sometimes rife at localities paleontologists know as microsites - dense accumulations of small fossils that can act as a census of who lived in the area during a given slice of time. Paleontologist Jaime Villafaña and colleagues sifted through more than 600 pounds of sediment from such a microsite in Chile to uncover what life was like along the region’s Miocene coast.

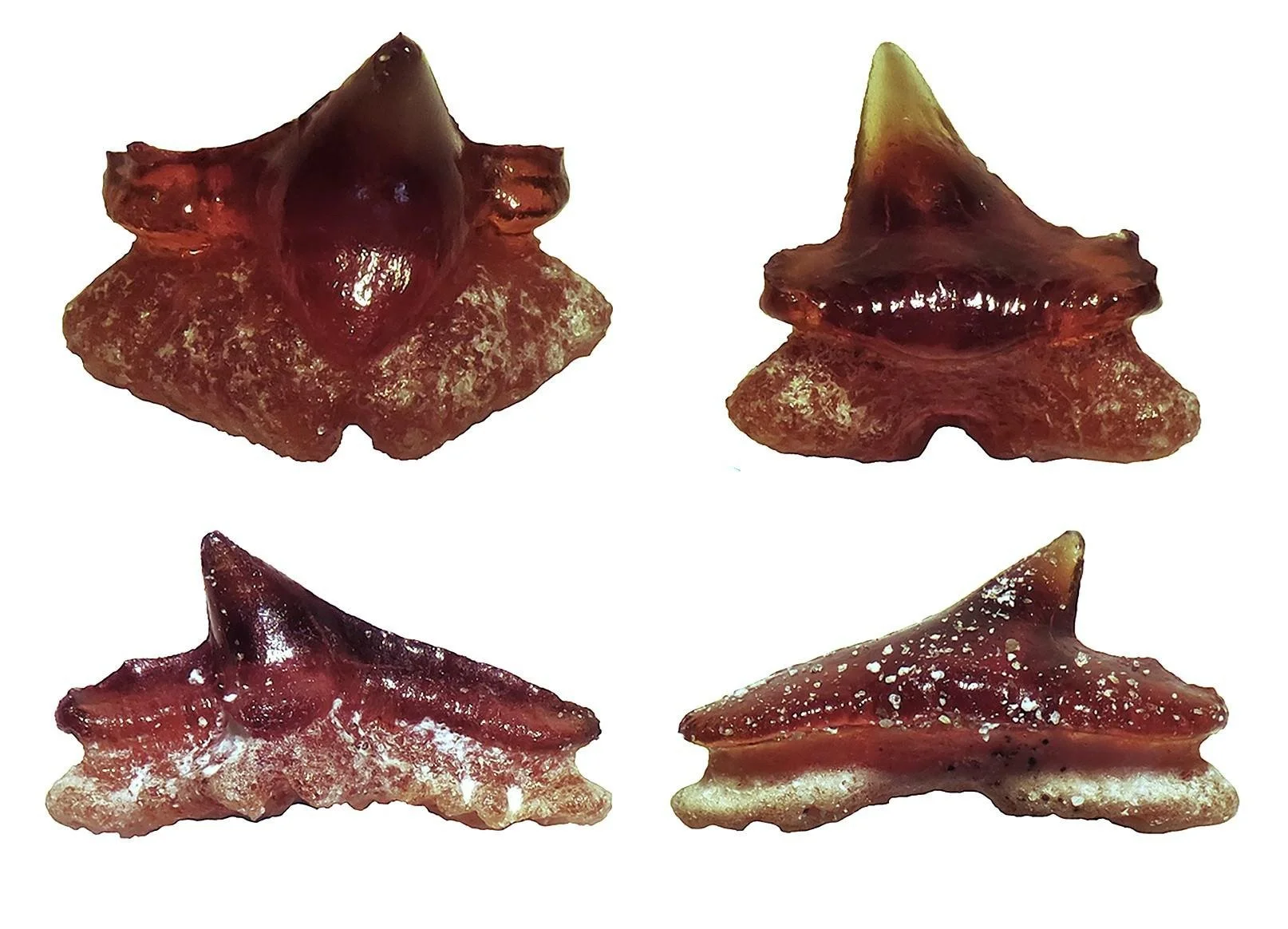

Some of the teeth in the sample were familiar. Villafaña and colleagues found teeth from basking sharks and leopard sharks - species alive today - that had never been uncovered in Chile before. The researchers also uncovered teeth from several different prehistoric rays that had not yet been found in the 7 million-year-old rocks of South America, as well as two new species. One is a new stingray, and the other, represented by a collection of nine small teeth, is Pochitaserra.

Several teeth of Pochitaserra found in Chile. Courtesy Jaime Villafaña.

The tiny teeth help fill out the fossil diversity of prehistoric Chile. Even though shark and ray teeth have been found in the area for decades, larger teeth are easier to spot than smaller ones. (Paleontologists know this as collector’s bias, when the complications of prospecting for fossils might alter what we know of an ancient ecosystem.) The smaller fauna was missing, leaving an essential chunk of the prehistoric ecosystem obscured.

Smaller creatures, which often feed on even tinier organisms, algae, organic detritus, and otherwise help form the base of ancient food webs are important finds even if they don’t impress us with their size. The lives of large, charismatic animals cannot be fully understood without uncovering how their lives were connected to those of smaller species that shared the same habitats. Not to mention that the discovery of an ancient sawshark in the fossil beds will help experts keep an eye out for other sawshark fossils in other localities. Sawsharks still swish through the bottom waters of our modern oceans, after all, and each fossil find fills in a little more of their backstory.

Villafaña and colleagues will undoubtedly learn even more about Pochitaserra and its fishy neighbors with additional study, but, most of all, I’m glad the researchers took the opportunity to do something fun and a little silly with the shark’s name. Scientists constantly complain about lack of public engagement with science and the stereotype that scientists are mostly old grumpy white men with bad hair. Acting stuffy isn’t going to change that. But doing something relevant to another nerdy passion, sharing an affection for art through science, maybe that’ll help spread some curiosity about ancient life and how we’ve come to know so much about it.

We now know the teeth of Pochitaserra, and with that we can share our ancient dreams.

This blog is kept free for the curious. If you enjoyed this piece, consider buying me a coffee or picking up one of my books!