Dinosaurs Were Weirder Than We Ever Imagined

Not only is Spicomellus the oldest known ankylosaur, but it’s one of the spikiest. Credit: Matthew Dempsey

Frustration and joy are tightly entangled in paleontology. Every incomplete fossil raises the question “Where’s the rest of it?” and museum collections are rife with mystery fossils that suggest something undeniably strange is still out there - if the fossil record’s been kind enough to safeguard it for us to find. To pull but one example from the ancient depths, consider a pair of Triassic teeth given the name Kraterokheirodon found in Arizona’s Petrified Forest National Park. I’d love to give you some idea of how the animal behaved, what it looked like, or even what sort of creature it was, but despite more than a century of fossil research in the area no one has found a single bone that corresponds to the teeth. Beyond “vertebrate,” we have no idea whether Kraterokheirodon was a dinosaur, crocodile, amphibian, protomammal, or what.

So when paleontologists Susannah Maidment and colleagues named Spicomellus afer in 2021, I made a mental note of the mysterious fossil but expected it might be decades, at minimum, before the rest of the animal was uncovered. The key fossil was a rib with large spikes fused to the outer edge. The best fit for the fossil’s identity was ankylosaur, which would make Spicomellus the oldest representative of its armored dinosaur family, yet the singular bone’s anatomy was strange even within its family. The fact the spikes were fused to the ribs, instead of growing in the skin, was “an unprecedented morphology among extinct and extant vertebrates.” In other words, no other creature living or dead has been found to have spikes like this. “Ankylosaur” seemed a good fit for the animal, but a knobbly rib isn’t much to go on.

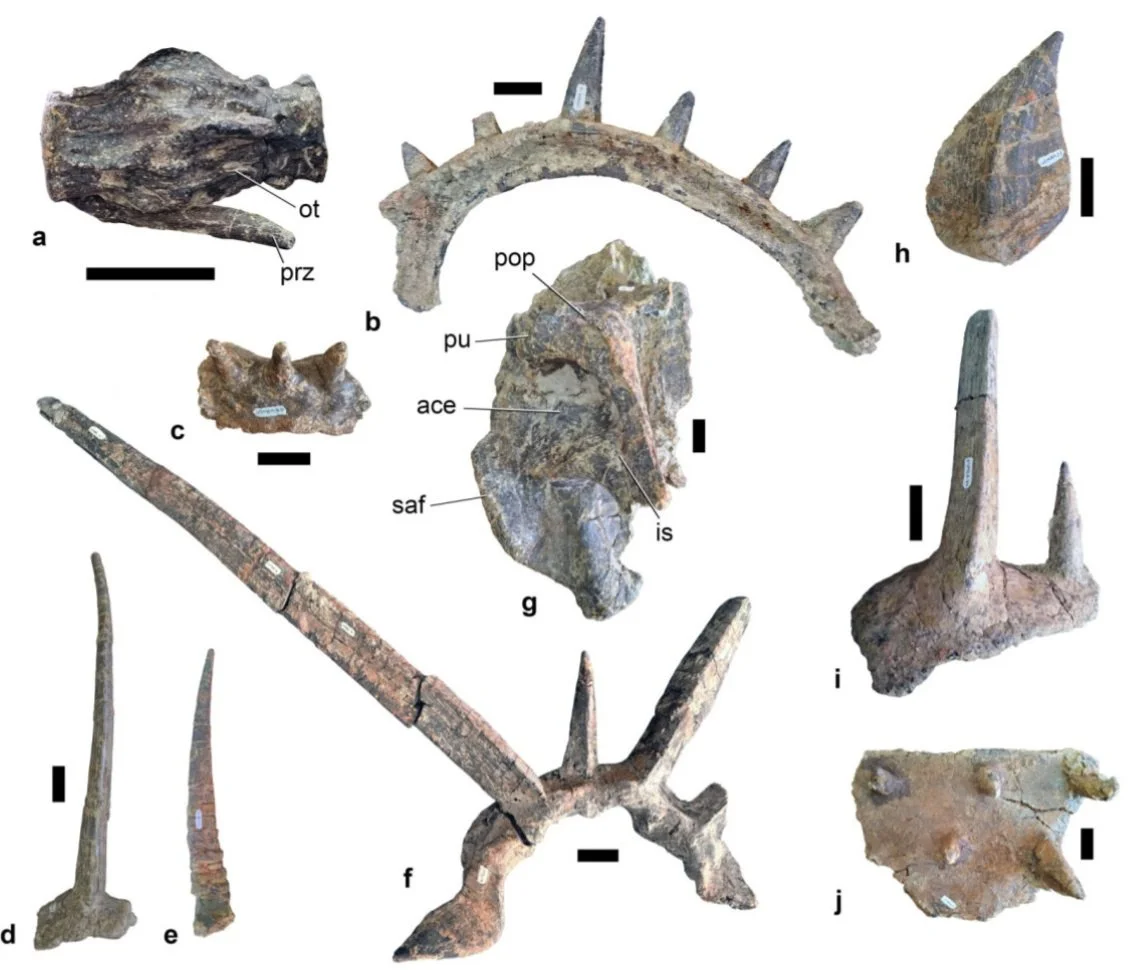

And so, earlier this year, I was happy to have my expectations contradicted when Spicomellus reappeared in the pages of Nature. Maidment’s original assessment of ankylosaur was correct, supported by a partial Spicomellus skeleton consisting of a skull piece, a smattering of vertebrae, six spiky ribs, hip elements, “numerous plates,” pointed osteoderms, and, most impressive of all, a cervical ring so studded with spikes it looks like the kinds of collars I like to wear. Spicomellus lived approximately 100 million years before the famous Ankylosaurus and yet it was just as studded with bone armor.

Fossils of Spicomellus, including the spiky cervical ring. Credit: Maidment et al., Nature (2025)

Prior to the discovery of Spicomellus, the early days of ankylosaur evolution seemed pretty hazy to experts. Paleontologists already knew that the broader group from which both plate-backed stegosaurs and club-tailed ankylosaurs evolved, technically called thyreophorans, had already originated by the earliest parts of the Jurassic, about 196 million years ago. Scutellosaurus, named four decades ago from fossils found in Arizona, was a small, bipedal dinosaur that had rows of pebbly osteoderms on its back. The armored dinosaur Scelidosaurus, found in England and also Early Jurassic in age, implied a quick increase in body size among armored dinosaurs prior to the emergence of armored giants like Stegosaurus and early ankylosaurs like Mymoorapelta found among Jurassic floodplains about 150 million years ago. The progression seemed simple, from small, armored bipeds to larger, quardrupedal herbivores that gradually developed their armor in different ways.

Spicomellus changes the story. The dinosaur lived in what’s now Morocco, about 165 million years ago. It is at least 15 million years older than what were previously considered surprising Jurassic ankylosaurs, and yet even at this early date Spicomellus shares key features seen in ankylosaurs that didn’t evolve until the next geologic period. Spicomellus had a spiky hip shield like that of the Cretaceous Polacanthus, and, on top of that, had tail vertebrae that made a sturdy “handle” in front of a club, a feature that had previously been thought to evolve about 30 million years later among Cretaceous ankylosaurs. Many of the later armor features seen among ankylosaurs, Maidment and colleagues point out, were already present in Spicomellus, hinting that the ornate armor of Cretaceous ankylosaurs may have been simplified compared to their ancestors.

The story of Spicomellus isn’t unusual in the annals of dinosaur studies. The “terrible hand” Deinocheirus was named in 1970 and presented as an enigma in the dinosaur books I devoured as a child. Imagine my joy when I was in the room to see the entire animal’s body revealed during the 2013 Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting, the presentation revealing that those impressive arms were connected to immense body of a shovel-beaked, sail-backed, fuzzy herbivore. And while the dinosaur Spinosaurus surely needs no introduction at this point, I remember playing with Spinosaurus toys and gazing at Spinosaurus art that presented the dinosaur like an Allosaurus was a sail glued on its back. Since 2014, however, we’ve received a new image of an awkward, paddle-tailed, croc-faced giant. When paleontologists eventually - hopefully - announce what the rest of the mysterious Therizinosaurus looked like, the only thing I feel sure of is that the dinosaur’s going to look stranger than we expect.

Finds like Spicomellus are not one-offs. Dinosaurs continue to defy our expectations because we are engaged in the same form of enthusiastic reconstruction that led 19th century scholars to think of the same animals are giant iguanas, rhino-like reptiles attempting to mimic mammals, and hot-blooded pouncers, dinosaurs continuing to change with the roll over of each year and each generation. We can hardly blame early anatomists for what they got “wrong” about dinosaurs. Paleontology, after all, was born from the combination of geology and comparative anatomy. Even though we can say we live among dinosaurs today, in all their avian glory, a seagull is not a Spicomellus and a chickadee is not an Iguanodon. Non-avian dinosaurs flourished in so many different forms that we haven’t even found and categorized them all yet, many species represented by single bones and fragmentary specimens, to say nothing of unknown species still in the rock and awaiting preparation as they rest in their plaster jackets. The finds we’ll witness in coming years will not only refine and adjust, as if we have a stable outline and are merely picking up refinements. The lesson the fossil record teaches us over and over again is that dinosaurs will defy our expectations at every turn, surprises constantly rewriting and reconfiguring our image of what these saurians were like during the hundreds of millions of years they flourished across our planet.

I can’t wait to see what we find out tomorrow.